Josephine Galadima had long dreamed of being a mother, so, when she conceived her first pregnancy in 2020, her joy knew no bounds. But her dream of motherhood fell through five months later, when she suffered a miscarriage.

Two years after her tragic experience, Galadima conceived again. After a long wait, she joyously welcomed a baby boy into her life. This joy was only short lived; her child began to develop severe fevers at three months old.

One night, just as Galadima was about to lay her baby to sleep, the infant started crying nonstop. She pressed her hand to his forehead; his body was hot to the touch. She promptly called on her husband, and he hurried to the Primary Healthcare Center some 250 meters away. Unfortunately, the facility was locked. He dashed to the house of the senior staff member of the facility, but he didn’t find him.

When her husband returned, Galadima saw that his face was etched with disappointment. “We have to go to the general hospital in Karim-Lamido,” her husband told her.

That night, Galadima and her husband embarked on an arduous journey from their village, Zoh Dutse, to Karim-Lamido town in northern Taraba State. A heavy rain fell as they trekked in the dark, drenching them and leaving the baby worse.

They would arrive at the hospital at dawn, where a medical doctor diagnosed the child with malaria.

“Desperation gripped me, and I told the doctor to do all he could to save my child. I promised to pay all the expenses,” Galadima recalled.

No sooner had the hospital staff begun treatment than the child died. Galadima and her husband felt their world fall apart.

The next morning, they hopped on a motorcycle back to their village and broke the news to the community, who mourned with the grief-stricken couple. Galadima believes that her child may have survived if they didn’t travel so far to Karim-Lamido, and if the health center in Zoh Dutse was operational.

“We suffer a lot here during pregnancy and childbirth due to the lack of access to healthcare. Many women here want to give birth but they are afraid of the struggles and lack of access to antenatal care,” Galadima told Prime Progress.

In her grief, Galadima dreamed of holding another child in her arms.

Falling apart

In 1999, the Taraba state government assigned a primary healthcare center to Zoh Dutse, a settlement in northern Taraba. However, there was hardly any structure in sight. Left in the lurch, the community pooled resources to build a hut as a makeshift health facility.

But the health facility lacked employees. Many of the healthcare staff employed at the facility shirked their duties. Some assumed duty on the first day, never to return.

Undeterred, the residents of Zoh Dutse rallied again to build a more substantial facility. The expanded building would be a modest bungalow comprising four rooms, a waiting area, pharmacy room, two wards, and a staff office. As in the first, the residents erected the new structure without aid from the government.

The walls within and outside remain un-plastered. Even with a roof, there are no ceilings. Two beds, a few chairs and tables, all bought through contributions from the community.

Data by Connected Development culled from 90 Primary Healthcare Centers across the country highlights the Nigerian government’s inattention to infrastructural development. These primary health centers confront challenges from severe understaffing to lack of electricity. Some PHCs are cut out from the national grid. In addition, 28% of the Primary Healthcare Centers lack access to clean water, resorting to unclean sources like rain and wells. This data identifies Taraba among the states facing a critical shortage of functioning healthcare facilities.

Licensed by the Nigerian Ministry of Health as a primary healthcare center, the Zoh Dutse Health Post is dilapidated, understaffed, and ill-equipped, severely restraining adequate healthcare to the community.

These issues paint a stark reality, compared to the services listed on the Thehospitalbook website, like antenatal care, immunization, and maternal and newborn care.

During a recent visit, this reporter found out that the facility had been under lock and key for months. A volunteer who has been here for more than a decade supervises the facility, according to community leaders. But other commitments cause him to travel outside the community frequently, leaving the village stranded in his absence.

Nuhu Samuel is the village head of Zoh Dutse, and he admitted to receiving government-provided medications once, nearly two decades ago. Since then, the facility has relied on funds raised by residents for medication purchases.

“We are lacking even basic equipment like beds, we used to have a few staff and offer services like immunization in remote areas,” said 51-year-old Samuel, who also serves as the primary healthcare committee chairman. “Unfortunately, due to the lack of support, those services are no longer available, and we are experiencing an increase in child and maternal mortality rates.”

Feeling the pains

Like Galadima, Christiana Danjuma faced challenges during childbirth. In 2019, while expecting her sixth child, she lacked access to antenatal care as there were no functional health facilities nearby. This pregnancy was different, however.

A few weeks before her expected delivery, Danjuma fell ill. The local health facility in Zoh Dutse was no help, forcing her to embark on a grueling 4-hour journey by foot to Bambur General Hospital, along with her husband

“It wasn’t an easy journey. I can still remember the pain. But we persevered, reached the hospital, received medication, and then returned home,” Danjuma, now 38, recalled.

Three days before labour, Danjuma’s fever returned, necessitating another trip to Bambur. This time, she traveled by motorcycle, got treated and delivered her baby safely.

“Since then, I haven’t gotten pregnant again. As for the fever, it continues to disturb me from time to time,” she expressed.

Many such journeys don’t often end happily. Plenty of women lose their lives or witness the heartbreaking loss of their children while desperately trying to access medical care. Often jobless and without income, these women struggle to afford healthcare at distant facilities, as it costs heavily to travel to these locations.

As of 2018, a high number of infants in Taraba died before childhood. This is shown by the child mortality rate, which sits at 70 for every 1,000 live births.

Samuel shared that when someone in the community, especially a pregnant woman, is seriously ill, their only options are Bambur and Karim-Lamido, which take roughly 2-hours on motorcycle. Yet the journey could take even more during the rainy season when the road becomes flooded.

“Sometimes, we travel in groups and even rely on the kindness of strangers to help us through the difficult path,” he stated.

Not only Zoh Dutse

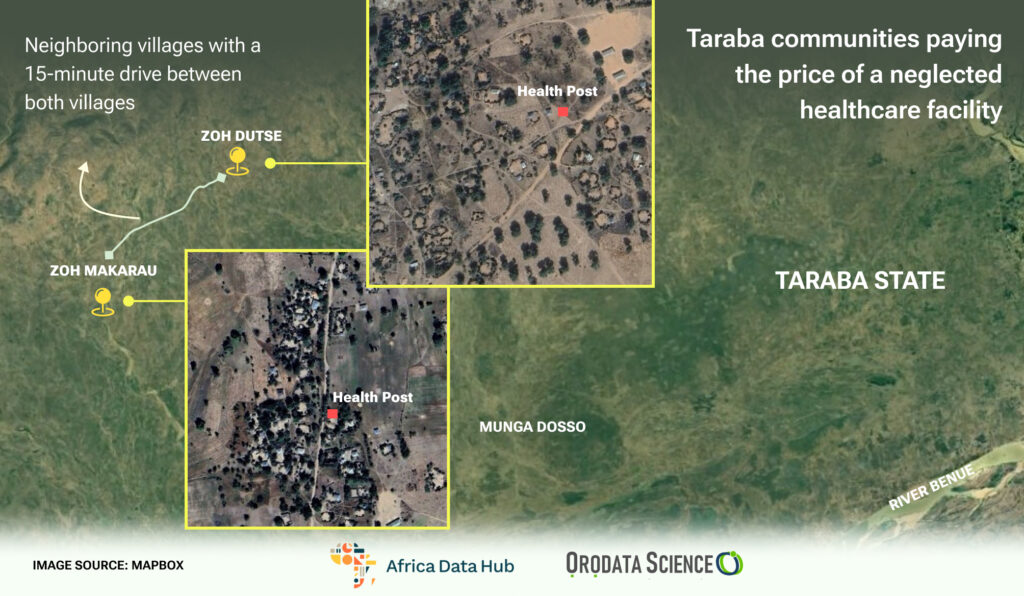

15 minutes away from Zoh Dutse sits the Zoh Makarau Health Post. This is still in Karim-Lamido. There’s neither a fence nor a gate.

There are four rooms within. Upon entering, a waiting room offers visitors a sense of discomfort with fewer than five ramshackle wooden chairs, which are threadbare. The ground floor, once covered in plaster, and the walls, which were once painted, along with the deteriorating ceilings, now display the effects of age and are desperately seeking renovation.

The medical ward by the right is no better, with only two beds fitted with threadbare mattresses. A few steps back, to the left, leads to the consultation room, which doubles as an office. There, two health workers spend their day attending to patients, whose problems they may never solve since there are no medical supplies.

Outside of this makeshift office, a narrow passage leads to a small pharmacy room with barren shelves. They haven’t held drugs for months. Outside the facility is an open field, bordered by dry grass, and notably lacking a proper toilet.

Although this is the only healthcare facility in the community, it falls short on many fronts. This reporter found only two healthcare staff workers operating in the facility, a volunteer and a Community Health Extension Worker, or CHEW.

“The government healthcare workers used to be here, but they stopped coming two years ago,” said Damisa Amenity, the CHEW responsible for immunization services through a contract with Gavi Alliance, a nonprofit organization.

A collective heartbreak

For 65-year-old Adamu Baba, growing up in Zoh Makarau meant journeying to Bambur for essential healthcare services.

“In these difficult situations, we lost many lives in this community due to the poor state of our local health facility,” Baba lamented.

Sharing his ordeal, Baba recounted battling an ulcer in 1991, which required him to travel a 300-kilometer journey to the University Teaching Hospital in Jos, to obtain treatment. Even now, taking his wife, who suffers from hepatitis, to the Federal Medical Center in Jalingo for treatment is challenging, because of shrinking harvests.

Amina John, a mother of three, further bemoaned the lack of qualified healthcare staff and medical equipment in the facility. “There are not enough qualified staff to meet our needs, and I often experience severe fevers during pregnancy,” she said.

The situation appears even more dire for mothers like Maryam Masadu who go to sleep every night with the heartbreaking reality that they can no longer conceive. Masadu got to know this 7 years ago, from the doctors at Bambur General Hospital, after she lost her fourth child.

“My child died because of inadequate healthcare here and it’s even more saddening to know that I can’t have more children,” she stated.

Since the government-appointed staff are largely absent, Amenity currently shoulders the responsibility for all healthcare services at the facility, struggling to procure medications for patients. Yet, for cases beyond fever, like pregnancy or childbirth, he refers the patients to Bambur and Karim-Lamido General Hospitals.

Time to take action

The community head of Zoh Makarau, John Joel, urged the authorities to intervene and provide their communities with essential healthcare services, qualified staff and medications, including improved facilities.

“We are also begging them to build good water systems around the healthcare facility. Our communities deserve better and relying on distant towns for healthcare shouldn’t continue to be our reality,” Joel stressed.

Residents of Zoh Dutse and Zoh Makarau urgently demand action from authorities to address challenges at their local health facilities, the primary source of healthcare for over 4,000 people.

Public health expert and founder of Sauzar Health Foundation, Abusufyan Ayyub, echoes the urgency for swift action. “Authorities should be aware of these problems and their intervention should involve establishing strong monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, as it will help in ensuring accountability in the implementation of the interventions aimed at reawakening the healthcare facility,” Ayyub explained to Prime Progress.

Mallam Bello Kakulu, a director at the Taraba State Primary Healthcare Development Agency or TSPHCDA, pledged to address the shortcomings at the two facilities. He confirmed the agency’s lack of knowledge about the situation and emphasized its mandate to improve healthcare delivery across far-flung communities.

“Having learned about your findings, I have spoken to a director of the TSPHCDA agency in Karim-Lamido. We have initiated discussions and will collaborate to enhance infrastructure and guarantee a steady supply of medical equipment,” Kakulu affirmed.

This story was produced for the Frontline Investigative Program and supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.