Zainab Mujahidu sits quietly under a tree on the grounds of Usmanu Danfodiyo Teaching Hospital, away from the group of women that were chatting nearby. Her eyes are fixed on the dusty ground, her thoughts weighed down by hunger, trauma and despair. It is nearly noon, and she has not eaten since the previous night.

Her 5-year-old grandson Saddiqu lies in the hospital bed just a few meters away, broken, wounded and fighting to recover from the sextual assault that took place in their home town of Illela Amarawa.

Zainab is still shaken by what her grandson endorsed. “He was raped” says Amina her teenager daughter, as she sits beside her mother after sharing a simple meal of two loafs of bread and sachets water bought with help from a kind stranger.

According to Amina the incident occurred on what was supposed to be an ordinary morning. Saddiqu left the house as he often did but did not return until evening. When he finally came home he was crying uncontrollably bleeding from both his nose and backside. He could barely walk.

Panicked, the family rushed him to the nearest primary health center (PHC ) but there was no assistance, no equipment, not even drugs to ease his pains,” Zainabu said, her voice cracking. “They said we should find our way to Sokoto.

Saddiqu is one among hundreds of patients shuttled daily from under-equipped PHCs to overcrowded secondary and tertiary hospitals across the state. In many cases, the delay in treatment proves fatal.

As the state’s healthcare system groans under the weight of preventable illnesses, frontline workers and health advocates warn, the cracks at the bottom of PHCs are widening into gaping chasms, costing lives.

A CRITICAL FOUNDATION CRUMBLING

Primary Healthcare Centres are designed to be the bedrock of Nigeria’s health system, they are the first point of care for common illnesses, maternal services, immunizations, and minor emergencies. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a well-functioning PHC system can reduce hospital admissions by 30-40 percent

A 2024 assessment by Orodata CheckmyPHC In Sokoto, a shows that over 60 percent of its 793 registered PHCs lack basic infrastructure, staffing, and supplies necessary to deliver even minimal care.

From broken beds to absent laboratories, the story repeats itself in Dange Shuni l, Illela, Yabo, and Bodinga LGAs. In a state where over 80 percent of the population lives in rural areas, the collapse of PHC services means dangerous and often deadly journeys to distant city hospitals.

NUMBERS THAT TELL A GRIM STORY

Findings reveal that in 2024 alone, over 73, 815 patients were referred from PHCs to secondary or tertiary hospitals.

67 percent of referrals were for conditions like malaria, diarrhea, minor injuries, or normal pregnancies ailments typically manageable at PHC level.

Only 12 percent of PHCs have functioning ambulances; most referrals are made without transport support, forcing families to improvise.

According to a report 2023 by the Nigeria Health Watch found Sokoto ranking among the bottom three states nationwide in PHC infrastructure readiness.

“We are overwhelmed,” said a Gynecologist doctor who pleaded anonymity at UDUTH. “Patients come here for malaria, ear infections, or normal labor , things a community nurse should handle. This delays critical surgeries and emergency care.”

THE HUMAN COST OF DELAY

Luba Buba, a 53-year-old mother from the Basasa community in Kware, shares how her son met a tragic fate during a communal clash between Basasa and Gidan Aiki villages,20 years old Yakubu sustained a severe head injury. Despite being an innocent bystander, becoming a victim of circumstances.

On that fateful Thursday morning, Yakubu had finished ironing his clothes with a local charcoal iron, planning to visit his sister in the nearby village of Umaruma. Before heading out, he decided to check on his farm, where he unfortunately encountered the fighting crowd. Rushed to the Kandam Gari PHC, Yakubu’s condition couldn’t be managed due to the lack of basic medical equipment.

The family was referred to Kandam Ta Daji PHC, but again, they were unable to provide the necessary care. It wasn’t until they reached Kware General Hospital that Yakubu’s wound was treated, and he was subsequently referred to Specialist hospital (UDUTH) for further treatment.

Dr Muhammad Sani, medical doctor with Uduth, said that in the medical field, time is often the most critical factor in saving lives, especially in cases involving bleeding. Whether from accidents, childbirth complications, surgical wounds, or internal hemorrhage, uncontrolled bleeding can rapidly lead to shock, organ failure, and death.

He said the body can only compensate for blood loss up to a certain point, after which the damage becomes irreversible. Immediate medical attention can mean the difference between life and death, and yet, too many lives are lost simply because help came too late.

Delayed treatment in bleeding cases is particularly dangerous because symptoms may be misleading. A person may appear stable initially, only to deteriorate rapidly as internal bleeding progresses unnoticed. In rural or underserved areas, where access to emergency care is limited, this delay is often fatal. Even conditions such as postpartum hemorrhage which is a leading cause of maternal deaths can be prevented with prompt intervention, yet remain deadly when patients arrive late at health facilities or face delays in being referred from primary to secondary care.

“As a healthcare professional, I urge individuals, families, and community leaders to prioritize quick medical response when faced with any form of bleeding. Do not waste valuable time with home remedies or wait to see if symptoms improve. Bleeding is a medical emergency, not a wait-and-see condition. Improving awareness, strengthening emergency transport systems, and equipping primary health centers to respond quickly are key steps we must take to save lives across our communities”

A story published by the punch newspaper on the 8 of March 2024 reported that the rate of maternal mortality in the Sokoto state stands at 1,200 deaths per 100,000 live births, one of the highest rates in Nigeria, where the national average is 512 deaths per 100,000.

Child mortality fares no better as 1 in 8 children in Sokoto dies before their fifth birthday while Malaria remains the leading killer. A disease that should be preventable and treatable at local health centers.

Alhaji Ahmad Garba Shuni, 63, has recounted the harrowing experience of trying to get medical help for his pregnant wife at Banga Nange Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) in his Dange Shuni community. According to him, his wife was experiencing severe pregnancy complications, but the PHC lacked the capacity to handle the situation.

“She couldn’t get the medical attention she needed,” he lamented. “The only option was a referral to the Specialist Hospital in Sokoto, A 33-kilometer journey that worsened her condition.”

The family was left with no ambulance service. “I don’t own a car, and hiring a taxi to Sokoto was beyond my means,” he said. “So, we had to rely on a Keke Napep (commercial tricycle). You know how unstable it is. The road is also in terrible condition. By the time we reached the hospital, my wife was in so much pain she began asking for forgiveness, thinking she might not survive.”

Despite arriving at the Specialist hospital, they faced another ordeal of a long wait before she could be admitted.

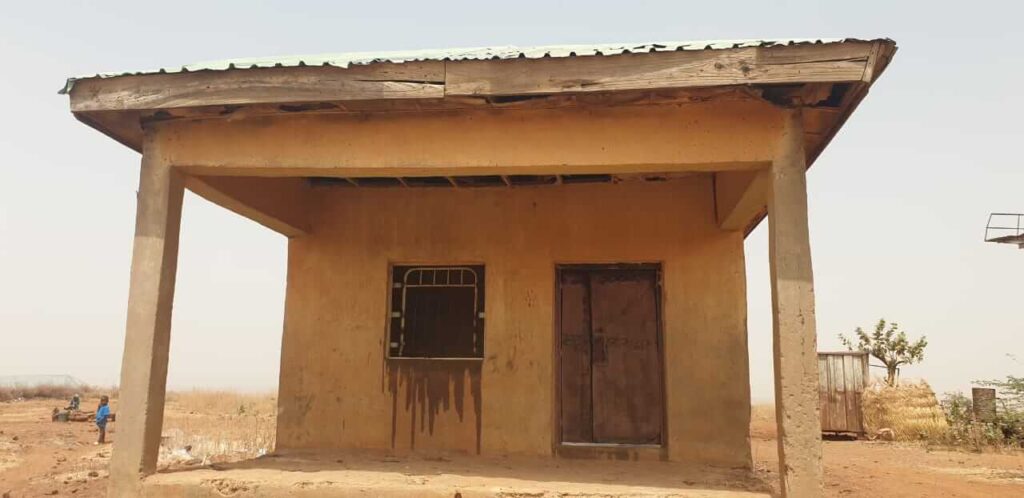

When this reporter visited the Banga Nange PHC, the facility had only two rooms, no fence, no hospital beds, and lacked essential medical equipment. The center is manned by only two health workers.

Abubakar Arzika, a Community Health Extension Worker in charge of the facility, was seen struggling to treat a young girl who had been hit by a motorcycle. Due to the absence of a hospital bed, the patient had to be held on her relative’s lap while Arzika attended to her all within a cramped space of just a few square meters. That single room doubled as the waiting area, pharmacy, nurse’s station, and ward.

BEYOND STANDARD

The National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) outlines that a standard (PHC) must be equipped with essential medical tools such as weighing scales, thermometers, stethoscopes, blood pressure monitors, and examination lights.

In addition to adequate equipment, each PHC should be staffed with at least one doctor, two nurses or midwives, and a number of Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) to ensure comprehensive service delivery.

PHCs are mandated to provide a broad range of services, including immunizations, antenatal and postnatal care, family planning, treatment of common ailments, and health education.

To serve communities effectively, these facilities should be located within a reasonable distance from the population they serve, in line with the World Health Organization’s recommendation of one PHC per 10,000 people.

Moreover, PHCs are expected to operate daily, with provisions for emergency services to ensure uninterrupted access to essential healthcare.

A visit by this reporter to the Alibawa PHC in Gada Local Government Area revealed a deeply troubling situation. The facility falls far below the standard expected of a functional PHC. Despite its mandate to serve several surrounding communities, the centre lacks even the most basic equipment necessary for patient care.

Sa’idu Abdulmutalif, a traditional titleholder and health worker at the Alibawa PHC, described how they resort to using containers to collect rainwater and prevent it from reaching patients, as the windows, roof, and ceiling are all damaged and offer no protection from the elements.

Pregnant women are left with no option but to deliver on a single worn-out mat placed on the dusty floor of the labour room or risk giving birth at home without any medical assistance.

THE MISSING LINK

Muhammad Yusuf Sharu, a public health advocate in Sokoto described PHC as the backbone of any resilient and equitable health system. According to him, PHC serves as the first point of contact for individuals, families, and communities with the health sector, and it plays a pivotal role in achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

“When PHC infrastructure is strong,” it reduces the burden on secondary and tertiary care facilities, lowers health costs, improves early disease detection, and enhances health equity.”

He said while over 70% of Nigeria’s disease burden can be managed at the PHC level, only about 20% of the approximately 30,000 PHC facilities across the country are fully functional as of 2023.

In Sokoto State, a joint survey by Nigeria Health Watch and BudgIT revealed that many PHCs lack basic amenities such as electricity, potable water, and essential medicines are the factors that severely hamper service delivery.

“When PHCs are weak or non-functional, patients bypass them and flood secondary and tertiary hospitals for conditions that could easily be managed at the community level such as malaria, uncomplicated diarrhea, or antenatal care,” Sharu noted.

“This creates a reverse pyramid of care, where the most expensive and resource-intensive facilities are overwhelmed with basic cases, compromising their ability to treat complex health conditions.”

He referenced a 2023 internal audit at the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital (UDUTH) in Sokoto, which showed that over 40% of outpatient visits were for primary care cases which resulted in overcrowding, long wait times, depletion of resources, staff burnout, and increased mortality from preventable complications.

Sharu outlined several interlinked factors behind the decay of PHC infrastructure in Sokoto and across Nigeria. According to him, only 5 to 6% of the national health budget is allocated to PHC services,” he said, “far below the Abuja Declaration target of 15%. At the state level, health spending is still skewed toward tertiary care.”

He also highlighted issues of fragmented governance. “PHCs are managed by local governments, many of which lack the capacity, funding, and autonomy to maintain them. Frequent transitions in local leadership and unclear responsibilities between state and local authorities have stalled investment.”

He said corruption and mismanagement further compound the problem. “Several audits by the ICPC and civil society organizations have uncovered ghost projects and misappropriated funds intended for PHC revitalization.”

Other challenges include workforce shortages and poor data systems. Sokoto has a health worker-to-patient ratio of 1:1,657 which is far below the World Health Organization’s recommended 1:600. Additionally, weak health information systems make infrastructure planning reactive rather than proactive.

WE LOSE FOCUS ON OUR MANDATE

Professor Anas Sabir the Chief Medical Director of Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital Uduth influx of rural dwellers into the teaching hospital is disrupting the institution’s core mandate of delivering specialized medical services.

“The arrival of rural dwellers or indeed anyone with minor health issues to the teaching hospital is placing immense stress on our system. In the Nigerian health system, we have a tiered structure of primary, secondary, and tertiary. As a teaching hospital, we belong to the tertiary level, where we are expected to offer only specialized services.”

He explained that, in an ideal situation, patients should only be referred to tertiary institutions after passing through primary and secondary healthcare levels. However, that referral chain is frequently bypassed, forcing the teaching hospital to handle basic cases like malaria, respiratory tract infections, and gastroenteritis.

“This is a hospital that performs open-heart surgeries, renal transplants, neurosurgery, and offers advanced oncology services. Our doctors are trained to focus on highly specialized cases, but when we are compelled to provide primary healthcare services, we lose concentration from what is expected of us.”

The CMD said that the hospital’s workforce including doctors, nurses, and other personnel is overwhelmed by cases that should be treated at the grassroots level.

“In most instances, these are ailments that should be managed at primary healthcare centers. But patients find their way here. And because we are a tertiary institution, we are trained never to turn down patients. So we attend to them, but it puts a lot of stress on our system.”

When asked why patients continue to bypass lower-level health facilities, the CMD acknowledged that the reasons are multifaceted.

“It’s difficult to pinpoint, but I believe one major factor is manpower,” he said. “We have more doctors, more nurses, better equipment, and most investigations can be done within the hospital. Patients see that they can get almost everything they need under one roof, without moving from one center to another.”

He added that for some patients, proximity to the hospital makes it easier to seek care there, even for minor ailments.

“Someone living nearby with a case of malaria may not want to visit a primary healthcare center. He may just walk into our facility. So yes, it’s multifactorial. But the key driver is the perception that we have more resources and in many cases, we do.”

He emphasized that the internal referral process within the hospital also contributes to its appeal. “If a patient is seen by a general doctor here and needs to see a surgeon, ophthalmologist, or cardiologist, the referral is immediate and within the same system.”

However, he warned that unless the referral system is enforced and primary healthcare centers are strengthened, the current situation will continue to overstretch the institution and dilute its focus.

“We are losing focus on our mandate,” he stressed. “Tertiary hospitals like UDUTH should not be reduced to treating minor ailments. It’s time to revive and empower primary healthcare services across the state.”

REVITALIZATION IS UNDERWAY

The Sokoto state Commissioner of Health Dr Faruk Umar in an interview with this reporter said revitalization efforts are currently ongoing across Sokoto State.

He said the effort is part of a collaborative initiative with the World Bank under the IMPACT project, which was launched in 2020.

“We are now in the final phase of the project, aimed at renovating 116 PHCs facilities across the 23 local government areas.

“Each local government will have a minimum of three and a maximum of four renovated facilities. These include PHCs, health posts, and clinics.

“The contractors are working according to the specified bill of quantities, which includes improvements to infrastructure, installation of solar power, provision of functional boreholes, and internal water reticulation especially within wards and maternity units.”

The commissioner said once the PHCs are revitalized, it will reduce the numbers of patients referred to larger hospitals.

“Functionality is key. When a patient sees a clean, well-equipped environment, they are more likely to seek care. In addition to infrastructure, we are also ensuring the availability of essential drugs. Plans are underway to procure and install basic medical equipment and instruments as part of this same project.

“That is why we call it revitalization, making these healthcare centers functional again.

WAY FORWARD

Despite the numerous challenges facing primary healthcare (PHC) in Sokoto, public health advocate Muhammad Yusuf Sharu believes the state can adopt successful strategies from within and beyond Nigeria to turn the situation around.

He urged the full implementation of the “Primary Health Care Under One Roof” (PHCUOR) policy to centralize governance and improve accountability. Sharu also called for better utilization of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), noting that only 38% of eligible PHCs in Sokoto had accessed the fund as of 2024 due to bureaucratic delays.

To bolster service delivery, he recommended forging partnerships with private providers and NGOs, scaling up the Community Health Influencers, Promoters and Services (CHIPS) Programme, and investing in digital health tools for real-time monitoring.

Sharu also highlighted the critical role of international partners in PHC revitalization. He said agencies like WHO, UNICEF, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation could provide technical support, funding, and infrastructure development. Organizations such as Médecins Sans Frontiers and Save the Children, he added, are well-positioned to assist in training health workers and reaching underserved areas.

He stressed the importance of civil society in ensuring transparency and community engagement, saying trust in PHC systems is essential for effective service uptake.

“Without a functioning PHC system, Sharu warned, “Nigeria cannot achieve Universal Health Coverage. The time to act is now.”

This story was produced for the Frontline Investigative Program and supported by the Africa Data Hub and Orodata Science.